Love and Madness Part IV

PART IV: CHAMPAGNE AND ASHES

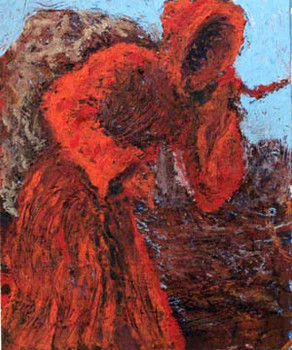

Self-Portrait 1987 oil pastel on 8x5 gesso board

CHAPTER FORTY

Fear stormed me when my father called before five on a weekday afternoon. Before I could question him, he said, "Patrick-a, please get down here as soon as you can."

The meaning of his words sucked out my air and dropped me to the sofa.

"Your mother's in intensive care. Congestive heart failure. She's holding on. Michael's already here and Maggie arrives at five. Make your reservation now and I'll call you back, and Patchey, leave the return flight open."

Agreement ended this awful conversation.

A hot ringing filled my ears as I looked up the airline number. I was again outside my body, as if I were watching myself book my seat. My sneakered foot was a blur at the end of my swinging leg.

The first available plane landed at midnight.

She'd be dead by then.

My injured foot fell to the floor, the shock of that pain unnerving me, hurling me back into my body.

A boneless despair enveloped me, disorienting me, triggering aimless anxiety. My eyes fled from object to object in my sunlit living room. I was stopped by a silver framed photograph of my parents.

I hurried to the kitchen and filled my glass with seltzer. I carried the bottle and my glass to the bedroom, darting through shadows that darkened the room, familiarity concealed.

Flyer curled on my breast when I settled beneath the comforter. I hugged her. She licked my face and hot tears sprang from my eyes. Suddenly I was choking.

Shock turned into electric joltings that made my skin crawl through chilling waves of fear.

I found myself dialing Susan�s number at work.

"Patricia, I'm taking you to O'Hare. As we speak, I'm putting files in my briefcase, telling Sally that I�m leaving and then I�m heading for your house. Why don't you start packing?"

"Don't hang up right now, please, Susan . . . "

"Your mother's fighting, your father said."

"But Maggie will be there, too. They've never had us in Florida at the same time before. Never. Don't you see?"

Call waiting bleeped, we said goodbye, I swallowed seltzer and answered my father's summons.

He said he wanted the whole family together, that he was tired. He never

mentioned fear.

Our exchange was brief and unmarked by tears.

His voice had sounded old, and uncertain, not like my father at all. I dropped the phone in its cradle. Mih-the was too young to die.

Anger absorbed my despair, anger so raw it frightened me. And then swooping anxiety turned anger into panic.

Lightheaded, shaking, I shook a Valium from the vial and swallowed it, focusing on Maggie. We hadn't talked in four years.

How was she taking this news?

Waves of despair rolled through me, anxiety cresting, not breaking. I couldn't let myself think about Mih-the.

Maggie stirred sentiments that were wary, and colored by antipathy. I didn't want to see her. Certainly not like this. Not now, not with Mother �

Punishing, back-heaving sobs, abrupt and awful, drowned the room in wounded sound. Flyer whuffed, and with hands that visibly trembled, I brushed the fur on her back with my palms, my cries diminishing, not yet subdued.

I had to pack.

I stared at the red room closet door, my purpose there momentarily forgotten. Urgent need prodded me to reach to the top shelf and grab a suitcase. I slung it on my bed and unzipped its compartments. As if by rote, I raided the bathroom medicine cabinet; I swept pills from my night table into a zippered bag. I collected vitamins and the morning�s Rx army from the kitchen drawer, sealing the vials in a plastic bag.

I was folding clothes when Susan rang the bell.

She offered to keep Flyer while I was gone. I hadn't even thought about her.

Throughout the flight, my constant fight to breathe tightened my muscles to a pitiless pitch. The endless flat blackness of star-pierced night filled the window. It looked as cold and as treacherous as the thoughts that flattened my feelings.

She'd be alive. She'd be dead.

Maggie would be there.

We'd be face-to-face.

Facing death.

The plane tilted nose-down. My stomach rumbled, it hummed and it heaved like bees meeting in their hive.

My brother Michael greeted me at the gate. He was alone.

"She's holding on," he said and hugged me. "And Maggie and Dad are in bed."

I almost missed the twinkle in his eyes acknowledging my relief that I wouldn�t have to face Maggie tonight.

I took his arm, watching our feet traverse the terminal.

"Cindy and I picked a good time to come down here."

"You sure did, but where are we all sleeping?" I cried, visions of sharing a room with Maggie tightening my throat�s existing constriction.

"Cindy and the kids went home this afternoon, Maggie's in the guest room, and I'm in with Dad, leaving you the office."

At the house we whispered good night and parted. Valium, lithium, Norpramine and Motrin flowed with renewed strength through my system. Slowly the rising tide of sleep raised me from the shoal of awareness.

"Good morning, Patrick-a," my father said, waking me and clasping my shoulder.

"Daddy," I cried, flinging my arms around his neck, wading through the haze of medication. "How is she?"

"She's still fighting. Hurry up and get dressed, we're going to the hospital."

It was six forty-five a.m. I staggered off the mattress, sleep starved and drugged, and dragged on pants and a shirt from the suitcase.

Maggie was in the kitchen.

I pushed myself across the threshold. "Hi, Maggie."

"Hi." Her tone was friendly. There was pain in her eyes.

"Did you see her yesterday?" I moved toward her and then turned my back to her, removing orange juice from the refrigerator. I filled a glass and swallowed each pill separately, straining to hear her answer.

"She looked really sick," Maggie said quietly. Her hair was short again, whorls of near-black traced by a few faint lines of grey.

"How do you think she really is?"

"I think she'll make it � the doctor didn't think she'd get through the night." Her voice withheld conviction.

"Let's go," my father said, allowing Michael to take the car keys. I couldn�t recall Michael ever driving when our father was in the car.

No one spoke on the ride to the hospital.

I stared at the back of Maggie's head. Family crisis forged the only link between us, a link strong enough to treat hostility. I inched forward until my elbow rested on the top of the front seat. I smoothed the curls that swung away from my brother's neck.

Maggie repeatedly clutched then released the oversized bag in her lap.

I sat back, eyes dropping to my own lap, to my own knotted hands. I forced my hands apart and took my father's hand. The face he turned to me looked so sweet, and so sad among his tired lines.

We were stopped at the doors of the intensive care unit. It was too early, the nurse said, pointing out the visiting hours sign.

"Her doctor will let us in before nine," my father wearily announced, turning back to the waiting room, sinking into a chair, as if his legs could no longer stand him upright. He looked grey, as if the room had infused him with its dominant color.

Maggie began working on the sweater she was knitting; her foot, crossed over a leg, kicked the air faster than her needles flashed.

Sweat oozed from my palms, my upper lip. My ankle throbbed, an aching hot insistence. Tears ran, hot desolation translating raw emotion. Alarm exploded in my mind, splintering fragments of breathless soundless screams, divorcing body, mind, sense. Up became down and down up, and everything in sight was separating. I clenched my eyes shut and still my vision switched and jump-shifted, colors flashing, like the delusion conjured by expressway panic.

"Patricia, sit up straight," I heard my brother demand as he gripped my shoulders with one hand, bracing my back with the other. "And breathe � slowly, one and two and, breathe, Patricia, breathe. In, out, in, out . . . good . . . "

"Don't you have a doctor down here?" Maggie asked me.

"Here's a quarter, Patrick-a," my father said, reaching into his pocket, handing me the coin.

Michael looked up Dr. Richard's home number and dialed, handing me the

receiver.

I stumbled through a description of the state of my mind, steadied by Michael's hand on my shoulder and by Dr. Richard�s voice.

He said he'd call the hospital pharmacy and order a prescription for Xanax, an anti-anxiety pill, he added. I was to take no more than six a day, and try to stick to four.

My brother retrieved the medicine and in his absence, I held my father's hand, practicing deep breathing, trying to reject thoughts that tried to pass through the doors of the ICU.

Xanax was a smooth and tiny lilac oval. It left a metallic bitterness in my mouth. Soon my emotions detached from my senses, making me an observer again, unable to participate. But breathing was still difficult: short breaths and shallow.

At seven-fifty, my mother's doctor arrived and authorized the nurses to let us see her, two at a time.

"You go first," I said, claws of anxiety unsheathing.

When my father and Maggie returned, Michael said, "Up and at 'em."

I rose, my knees a gelatinous bridge between thigh and calf. Faltering, I took Michael's arm and approached the oversized double doors to intensive care. Slowly they swung open.

Michael turned into the first doorway. The room was washed in twilight. It hummed and it clicked. It inhaled and exhaled. It smelled antiseptic. I hung back, eyeing the labyrinth of tubes extruding from my mother, her form inert and spread-eagled. Michael pushed me forward.

A hideous tinted-green mask covered my mother from nose to chin. A tube was shoved through her lips, forcing down one side of her mouth, garish and inhumane.

My mother dragged her eyes to meet mine. I didn't know what to say to her. Pressure to say something forced words out of my mouth: "I'm sooo glad to see you, I'm so glad to seeeee youuu," I cried, my voice careening up the scale of hysteria.

"Patricia . . . "

My brother's tone, and my own lack of control, sent me racing from the room, hand clamped to mouth to silence my screams.

"What's wrong?" Maggie cried when I reappeared. "Is . . . is she . . . ?"

My father came toward me.

I shook my head no and motioned them to take my place. Alone, I hurtled into a corner of the lounge, overcome by wrenching sobs.

In less than a month my mother had become a fragile and violated thin hull. The transformation was too great a leap, even under the ministry of Xanax.

"Are you all right?" Michael was beside me, cupping my elbow, turning me to face him.

"It was . . . too much � " I was shaking all over, new tears joining the old.

"It is shocking," Michael said, calming me, raising me from the floor, hugging me, helping me to the grey leather sofa. "You have to see her again," he insisted gently. "For her sake, and yours. Feel up to it now? No? Let's go for a walk outside. You can smoke a cigarette � if you have to . . ."

I limped after him to the bank of elevators and then out into the hot Florida sun.

All too soon it was time to retrace our footsteps. All too soon I was again at the foot of my mother's bed.

"You, you look like an astronaut with all this, this . . . " I flung out my arm to encompass the complicated-looking equipment. I found Mother's hand, frail and skeletal, and I held it in my own.

"I saw space yesterday . . . " my dear mother rasped behind the mask. And then she stared into my eyes. "Your hands are cold, honey, so cold . . . "

"Warm hands, cold heart, and you're warming me up like you always do."

The nurse said my mother needed to rest. Michael circled my shoulders with his arm and we left her.

After a hurried, near wordless lunch, we returned to the hospital. Now and then Maggie and I would go outside to smoke a cigarette. "Things are looking up," she said, backlit by the sun. "The doctor seems encouraged by the fact she's still alive."

"Are you?"

"She's going to come through this. And I can't tell you how much better she looks today than yesterday."

"I can't imagine her looking any worse. I can't imagine it . . . "

"Trust me," Maggie said, sparking the challenge that had divided our past.

"Believe me, I'd like to." I drew closer to her, stumbling, almost falling. I cried out from the pain that shot into my ankle and Maggie spanned the gap between us, gripping my arm, propping me upright.

Maggie helped me return to the lounge. The men in our family faced us from two armchairs as the elevator doors opened. We sat on the grey leather sofa, and I moaned, unable to muzzle my pain.

"Let me see that foot," my sister demanded, hovering while I unlaced the sneaker, removing it, and the sock.

"Let's see the other one," she prompted, examining without touching either foot. "The right one's swollen," she judged finally, sympathy in her tone. "What did the X-ray show?"

"I never went to a doctor."

"Oh, Patrick-a, how could you be so careless," my father exploded.

"It's just a sprain."

"I'll get her to a bone man on Monday," Michael said. And he went back to the phone and looked up the name my father gave him, calling and gaining an appointment.

Once more in the room with my mother, I watched drowsiness lower her eyelids again and again, despite her resistance. She hadn't slept since entering the emergency room yesterday at daybreak, she said.

The four of us dined in a restaurant near the hospital. Little was said. When it was time to leave, my father stood. My father fell face-first to the floor.

I whirled away from the horrifying sight, hiding in Maggie's comfort, unable to watch.

Michael was so solid in the face of collapse.

But it seemed like forever until Maggie said my father was in a chair.

Maggie and I rode home in the back seat of the car.

When Michael and Daddy went to bed, Maggie and I went to the terrace, sitting silently, smoking one cigarette after another, until there were eight in the ashtray. "How's the foot?" she asked.

"Not too bad." But it hurt. Oh how it hurt, how it pulsed hot and throbbing against swollen-stretched skin. And I knew that every pain I was feeling was centered in that ankle.

"What do you think happened to him?" I questioned, afraid of her answer.

"He's tired. He's been through a lot."

"Do you really think that's all it is? He's lost even more weight since early December."

"He's been through a lot," Maggie repeated with confidence and with firmness. "We should get some sleep, too."

On Monday, the critical stage was over and Mother was moved into a private room, its attractive furnishings oddly juxtaposed to the equipment that guarded her life.

Relief fed conversation as Michael took me to the ankle specialist. My foot wasn't broken; it should heal soon, the doctor said. He wrapped my ankle to the knee, the bandage to be worn three weeks.

My father looked gaunt; even his voice was thin, I noticed when we returned to the hospital.

On the terrace that night with Maggie, I again voiced fear for him.

"You worry too much," she advised.

"But you can see he's in rough shape. How can I not worry about him?"

"And you think I don't?" she snapped. When I flinched, she said, "Sorry. I'm on edge."

"It's terrifying."

"It was only Friday that the doctor was planning Mother's eulogy." Her shrug said everything.

When I darkened my room that night, I thought about my mother; I thought about my father. A plan began to form.

Waking was a slow emergence from a dark, comforting place. It was five-forty. I decided to call the hospital, my heart tripping to a faster and faster rhythm as I set my hand on the phone, still unable to believe Mother was out of danger.

Before lifting the receiver, I heard someone walking down the hall to the bathroom. I opened the door. My father seemed surprised to see me. And then he smiled.

"Did you call?" I asked softly.

"Yes. She�s doing okay. But I knew your mother wouldn't dare die before me. She's ten years younger and she has my best interests at heart." He shook his head; he smiled. "And I had a good night's sleep. How about you?"

"Daddy, I'm moving down here. I don't know why I didn't agree when you suggested it before." There. It was out. I couldn't retract it. "I'm going to lease my place in Chicago and rent one here � "

"I'm glad you want to come down, but first you have to finish the word processor course." His tone was inflexible.

"That's not till the end of May!"

"You can come down then," he said firmly.

"Okay, okay. Okay!" I hugged him. But it was only January. They needed me before the end of May.

He went on down the hall and anxiety claimed me; I fumbled for a Xanax and the water by the sofa bed.

While my father showered, I went through our conversation again and again, resolve strengthening. I wouldn't lose my home if I rented it. I wouldn't be committed to Florida. I could live anywhere as long as I could go home again. And I'd be near my parents, a walk away, faster by car.

When Michael and Maggie woke up, I told them my plan.

"The halt leading the blind," Michael teased and when Maggie laughed, too, I joined them.

Maggie left the next day, returning to Buffalo, city of our birth. Michael and I were going home Thursday. He'd finally convinced me that our father and mother could manage without us by then.

Susan thought the move to Florida was a good idea. Dr. Moline thought the move to Florida was a good idea.

I felt stronger than I could remember. I now had a reason to be alive.

On the flight back to Chicago, a short story began on a yellow pad. The story came slowly, a fictionalizing of Mother's congestive heart failure. I named it The Waning and in its writing I found solace. I found my true self, and an easing of horror.

The word processor came more easily to me, despite the missed week of classes.

Every day I packed two or three boxes.

My mother came home. Her cancer had been reduced by the chemo. So had her heart. She was feeling exhaustion not pain � the shingles had disappeared, too.

My anxiety was layered by three Xanax a day, not the six I'd needed in Florida, not the five, then four that I took my first week home . . . Home. The dismantling of my apartment gave it a strangeness that was unsettling, making abandonment desirable.

A married couple signed a lease during the third week in February on the condition that I paint my green walls white. It was no longer home once that was done.

============================================================

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

My father was nauseated.

He couldn't eat.

My father grew weaker.

When he was hospitalized for tests, my sister Maggie went to Florida.

Everything they put him through came back negative. The day after he got out of the hospital, Maggie flew back to Buffalo.

My father grew weaker. He needed a cane.

Michael, Cindy and I were in constant contact. Maggie and I spoke weekly.

My father grew weaker. He needed a walker.

I went back to six Xanax a day and increased my bedtime pills until they brought sleep to me. My breath was always short and shallow swallows of air, never quite enough.

A nurse came to stay with my parents. Her name was Barbara and she was big and strong, Mih-the said.

The word processor course took me into the Loop two times a week. Somehow I completed assignments, but when called upon in class, I couldn't remember what to do when.

I was relieved when Dr. Moline recommended that we see each other twice a week. His support reduced my fear by acknowledging its reality, as well as by acknowledging the awful limbo of new unanswerable questions.

Between sessions and school I packed, ink-stained from endless skeins of newsprint. My home became a series of paths through columns of stacked boxes, each filled, taped and identified.

Packing certain pieces took me back to moments of first possession, times of hope, hope that was bright before death became personal.

Packing was tedious. It gave me too much time to think. I packed thirty minutes, forty, took a break to write, call friends, pace, nap, walk Flyer.

It was the writing, it was the medication, it was the encouraging support of family and friends that pushed me forward. It was suddenly the last week in February.

My brother called. Our father had collapsed and his doctors didn't know why. He was in the hospital, undergoing more tests.

Michael said he had seats for us on a plane leaving at six and to meet him at O'Hare. Would Maggie be in Florida? I couldn�t breathe as I waited for his answer. She was leaving Florida that afternoon � she'd been down for a week's vacation, he reminded me.

I called Susan. She offered to take me to the airport; she offered to take Flyer.

Xanax chained me to the high diving board; I was afraid of its edge, the last foothold before the plunge into space.

It couldn't be that serious since Maggie was going home.

It wasn't that serious.

Maggie and I were in tune with each other now, allied by a common fear. And though she never asked about my writing or my friends, she did ask about my foot.

Since December, the foot had been swollen and painful. It would never get better I'd tell Maggie. Yes it will, she'd insist.

My father was home from the hospital when Michael and I arrived. We met Barbara, the nurse who now slept on a cot in our parents' room.

We went to see our father. He was propped by pillows and the raised head of the hospital bed. He was on Mother's side, next to the phone. This change chilled me and curled my stomach, muscles clenching so tightly that I couldn�t seem to fully catch my breath, almost losing the swift rise of bile that continued to sicken me.

His cane was in the corner, his walker parked within his reach. He smiled at us, returning our kisses. He didn't say much. Talking was difficult for him, my mother said, twisting the pain in my heart.

I took a seventh Xanax that night and woke in a drug-dazed fog. I added Xanax to my breakfast dose of lifelines.

Michael chauffeured our father to and from the hospital day after day. Those days seemed to swim by in a breathless hold of hope and fear.

My father grew too weak for the walker. A wheelchair was now parked by his bed.

When I looked into my father's eyes, the light of life was so strong that I'd forget how sick he was. But he wasn't sick, his doctors could find nothing wrong. He was just tired, just as his friends kept telling me. The disintegration of his body would stop; it always had. Oh but when?

There were no more tests for my father to take. He didn't dress again during that visit. Neither did my mother, but I was used to seeing her in one of her beautiful robes.

My father was alone when I went to sit with him one afternoon. He appeared to be asleep, but he opened his eyes and he smiled at me and, with effort, he raised his head; with effort, his lips worked, trying to form the word hello that finally came out into the open. "Hi, Daddy-O," I whispered. "You're pretty lazy these days, but I love you anyway, you know that, don't you?"

He nodded his head, and his smile when it curved into his face made me ache with love. But how could he just lie there? Why wasn't there a medical name for what was happening to him? "They say you have to use it or lose it � won't you walk with me?"

His head shook slowly, side to side.

"Oh Daddy, can't you?"

"Weak," he finally uttered.

He'd been so active. My stomach coiled, ready to erupt. I swallowed back the liquid rising in my throat and brushed his hair with my palm, sitting beside him, scratching the length of his arm.

He grinned. A full grin. His eyes lit up. He fumbled for his glasses and put them on. Oh how alive his eyes were in his tinged-grey face, cheeks sunken below the heaviness of his cheekbone.

"Patrick-a," he said, his voice rattling my name. And he held out his hand to me.

I took it. I gripped it hard. "Use it or lose it," I heard myself say again, and in the stillness of the room, my voice sounded harsh. "Oh Daddy, can't you try? Can't you? Come, I'll help you. You can walk around the bed � just in case you need to sit down fast!" I laughed, but it sounded hollow.

He nodded, turning back the covers. I helped him up, I slung his arm around my shoulders. I matched my step to his, one foot slowly forward, then the other. At the foot of the bed he gasped, he sank to the mattress, pulling me down with him.

"You were great," I cried, kissing his cheek, sitting beside him, huddled inside cold despair.

And then Barbara came in and she helped him back into bed.

After that, my father left his bed only to ride the wheelchair to the bathroom, never again to the kitchen for meals. And in my heart sprang the horror that I'd caused him to lose the last of his mobility.

I couldn't cry. I felt nothing but the droning sensation of drug-induced fog behind which lay unendurable alarm.

Dr. Richard exchanged Dalmane for Ativan � a different kind of anti-anxiety tranquilizer that would aid Xanax, he explained. It made sleep come quickly; it made time awake more distant, and therefore more bearable. I didn't see Dr. Richard that visit, but I spoke to him on the phone almost every day, time he never billed.

When Michael and I left at the end of the week, we still didn't know what was wrong.

I took a seventh Xanax along with the Ativan to get a grip on sleep, desperate for their tie to oblivion.

Back in Chicago, fleshing The Waning took me high on the seeds of creation, far away from myself and the tentacles of death that corrupted time when I couldn't sleep or create. But I also had assignments to complete for the word processor class and there were more boxes to pack, a trunk to buy, estimates to get from movers, people to see.

Oh my god what was happening to my father? But it wasn't cancer. It wasn't anything medical science could name.

Oh my god what was happening to him?

My mother was getting stronger.

My father was getting still weaker. He could no longer speak on the phone.

�Journey� came back from the agent in New York with a rejection letter. I left the manuscript in the mailer and shoved it under my bed.

Dear Jess,

Jessie? Oh Jess. My father is failing. He's losing his power of speech, and the use of his limbs. My FATHER, Jess. What does it mean that no one can find anything wrong with him? What DOES it mean? I can't stand this. Anything but this � I haven't feared his death since lymphoma first attacked him nine years ago � he's always gone into remission so easily. He�s NOT dying, he�s tired.

But he keeps losing more and more control over his body. My father's failing, Jess, and no one can help him. He's slipping. But he isn't going to lose to death. He wouldn't leave us in this harsh reality, my mother so sick, and as for myself � I can't let myself think about that.

I removed from the typewriter my letter to Jess and inserted the last page of �The Waning.�

The weeks churned in a blur driven by need to finish packing, to complete word processor assignments.

* * *

Thursday, March 26, l987, my brother called. He was coming down to Chicago to bring me and Flyer back to Milwaukee; we would take Friday�s seven a.m. flight to Florida.

"I could've met you at the airport, Michael."

"We didn't want you to be alone with the fact Hospice comes to the house now, and Nurse Barbara is still there . . . Dad has brain cancer."

"Is Maggie . . . ?" Hospice came to the house.

"She left today. Mother's doing okay."

Maggie left today. Maggie left today.

Our father hadn't left his bed in days, the nurse told me soon after Michael and I arrived in Florida.

Diapers dressed him and Barbara and Mother fed him, yet the life-light in his eyes was bright, illuminating his love and wisdom and humor. He wasn't near death at all, I realized, and escaped the lightening flash of recollecting my father�s friend Teddy�s cornball jokes the day before he died.

There was a hush upon the house of my parents I hadn't heard before. The phone rarely rang, that in itself seeming ominous in a home in which the phone always had seemed to ring. And voices within the house were hushed, and the feet that crossed the floors were rubber-soled or bare.

Family came to visit, and close friends, their stays quiet and brief.

Someone from Hospice came every other day.

Monday, March thirtieth, a woman from Hospice instructed Barbara to use an eyedropper to give my father water. An eyedropper, feeder for new-born birds fallen from the nest.

There was a liquid feel to the flow of time, perhaps owing to the medication I took. There was a sense of unreality as moments turned into hours turning into days and then into dreamless nights.

Maggie flew down Thursday. Late that afternoon, Mih-the, Maggie, Michael and I gathered on the bed around our dear Daddy-O. My father raised himself from the pillows and made a joke. It was the first time he'd spoken in days. Our laughter was hysterical. And lifted spirits were strong in every eye.

Friday evening, my father had trouble breathing, which seemed to me like an asthma attack. "Sit him up," I cried to Michael, to Barbara. But they wouldn't, and they wouldn't raise the head of his bed. Sitting up made breathing easier. Why wouldn't they listen to me? I rushed from the room in a fever of helpless fury. It was nine o'clock, but I drugged myself into sleep.

The next morning, Barbara knocked on my door and asked me to come see my father.

Rage stunned me when I heard her voice: She and my brother had kept my father on his back when he was fighting for breath last night.

I brushed my teeth, washed my face, brushed my hair, deliberately taking my time, postponing encounters with my brother and Barbara.

At the doorway to my parents' room I stopped. My father was on his back, his neck arched, his head thrown back, his nose and gaping mouth rising tight against skin stretched taut, as if he were gasping for air. He was whitened and waxen, not like my father at all. My mother was sitting beside him, holding his hand. "He's not . . . IS he...?"

"Come say goodbye," I heard Barbara say through a hot rush of wind that channeled disbelief and horror within.

I turned and ran, and ran straight into Michael. He ushered Mother and me into Daddy's office. My eyes were hot and dry and riveted on Mother, on her bone-thin slump and the dark fuzz covering her chemo-bared scalp. She was curled up on the sofa, hand entrusted to Michael. "He wasn't supposed to die first," she gasped, over and over and over.

Cancer had been a joint venture for my parents. That thought freshened my grief and I turned away from Mother, unable to witness her loss.

"I wasn't supposed to outlive him," she moaned. "Why didn't I die first? I want to die."

We rocked together, Mother and I, huddled under Michael's arms, the three of us laced together on the sofa.

I didn't cry. There were no tears. Death had cut me off from feeling. And no doubt medicine supported the void.

At some point my father's body must have been taken. At some point we sat at the table in the kitchen, making a pretense of eating.

Unshed tears were still locked inside me.

Maggie left the next day, a Sunday. Michael left Monday. I stayed with Mother through the following week, drifting through mourning together, sleeping together through night-sharpened pain, reading on the bed she'd shared with my father, hands interlocked across the king-sized expanse, consoled by each other and by medicated abyss.

Thank heavens I�d be living near Mih-the in little more than a month, that thought giving me a position in life. Before returning to Chicago, I found an apartment five minutes from her home. Hours before my flight and, for the first time since death took my father, Mother left her bed to see what I'd rented. She declared the neighborhood unsafe, and the rooms far too dark. She didn't see the beauty of the tropical forest backing the building, shading the living room, its fresh range of greens and occasional shafts of sunlight making me to oblivious to harsh Florida sun and cement. She said, "You're too impulsive, too hasty." She shook her head. "You must learn to STOP, and THINK before you act," she demanded, taking me to an apartment complex recommended by a friend. It was attractive but for the sameness of every row of housing, all facing an endless parking lot and each other; its landscaped bright, vivid floral arrangements mingled with trees, palms and shrubs, none of which could make up for the sea of asphalt just beyond them.

The living room was half the size of the one I'd rented, and it was more expensive, but it had a loft bedroom, perfect for desk as well as bed. And throwing a toy down the stairs would be great exercise for Flyer. I took the place, anything to pacify Mih-the.

Back in Chicago I went to class, did assignments; I finished packing. I tried not to think about the cramped quarters awaiting me in Florida. I not only gave away books and clothes, I gave away my beloved record collection and the Italian modern elephant grey velvet sofa and chair from the red room. There was no room in that box I'd rented in Florida, and I didn't have the energy to sell leftovers to strangers, or the funds with which to buy storage.

I called Jake. I needed the warmth of arms around me. I needed to bury the sight of my father's last gasp.

Jake said he was sorry about my father and then he launched into a litany of trips taken since we'd last spoken. There was no comfort in his presence, no compassion, no understanding, no mediation by passion of the watery emptiness floating within me. I left him and my half-finished drink, my goodbye curt, icy, unforgiving. He was a stranger in the end and it was as if our seven years together had happened to someone else.

============================================================

CHAPTER FORTY-TWO

Two weeks before I could exercise my lease in Florida, Flyer and I flew to Ft.

Lauderdale and moved into my mother's guest room.

My mother was weak. She weighed ninety-three pounds. Ninety; eighty-seven.

She rarely dressed, receiving callers in one of her elegant robes.

Yesterday, after her last CAT scan, her oncologist said she'd won her war against cancer.

Fear for her slipped away, leaving me giddy and lightheaded. When we stood to leave, my knees melted. Luckily, the arm of the wing chair propped me up until things stopped shifting and I could find my balance.

June first, I met the movers at my new apartment. My living room and dining room furniture now had inches instead of least feet between them. At least the loft wasn�t crowded, and I liked having my typewriter and desk a few feet from my bed. I liked it up there and never stayed downstairs without visitors.

When I returned to my mother�s for dinner, the table was already set for us, and dinner was on it. As we sat down to eat, I asked where Barbara was. My mother said that she had fired Barbara. A nurse was too expensive, she had too little to do, my mother said.

�But Barbara knows exactly what to do if anything � �

Mother straightened her back, her chin rose and she said, �I am the manager of my own life.�

She looked so small, too small for the tone of authority she had just used. Her eyes drew mine to them, reflecting the fire of her passion, that particular brilliance that lit every major event in my life. I was absorbed by her eyes, every look and gesture, every word she said sounding in triplicate. But she was free from cancer, safe at last. I would stick around until she recovered her strength and resumed her social life as a new member of the widows� club, which so many of her friends already had been forced to join.

The next day, my mother's housekeeper Paula phoned. She sounded close to hysteria when she described my mother's �drunken-like drive� to the grocery store. Paula wound up this news by begging me to come over and take away my mother�s car keys.

Not me, I said. Paula pleaded with me and I relented. But instead of going to my mother�s house, I called her doctor � she listened to him.

He said, "Why would she fire the nurse? With her short-term life expectancy, she doesn't need to worry about money." That said, he agreed to call her and tell her not to drive.

"Short-term life expectancy" slammed me. Again. And again. I reeled in this upheaval of fear. I dropped from the sofa to the floor, distancing my fear of falling. Flyer came to me but didn�t try to play. She understood.

Inhale. Exhale.

I grabbed the phone and called Michael, then Maggie. Both of them confirmed my worst fear. Her heart attack right after I left Florida after my dear-hearted father died had left her with thirty percent of her original heart. No one ever mentioned this fact.

What did short-term mean? Six months? A year? I was too afraid to ask.

Paula, Mih-the�s housekeeper, called me the next afternoon and said that my mother had the stomach flu and that she didn't want me to know.

Inhale. Exhale.

I called Mih-the and announced that I was coming over to visit, and along with my toothbrush, I brought Flyer.

"I feel lousy. Defeated," Mih-the said, seeming to me to be smaller than she�d been a few days ago. She stepped back and opened wide the front door. As I crossed the threshold into the cool shadows of her home, I gave her a quick salute and hurried to the kitchen, grabbing a glass, filling it with water, shocked by her appearance, by what she said, by the heat of my flushed face. In the weeks I�d stayed with her before moving into my rental, I must have not really looked at her, or noticed that she was shrinking. But worse than her appearance was the realization that not once in seven years of cancer had the words "lousy" and "defeated" littered her vocabulary. Not after her mastectomy, not after lung surgery. "I'm fine," she'd always say, smoothing her beautiful hair.

Two nights later, I was still at my mother's house, against her wishes. Flyer woke me up around four, jumping on the bed, nuzzling me, whining, jumping off, running to the door and back, repeating herself until I followed her and opened the door. Mother's light was on and, as I headed to her room, the small brass bell rang, the one that always told us when dinner was ready, the one that always tolled when we were sick in the night and needed help.

I was dazed by medication and interrupted sleep, but adrenalin surged within me, forcing me to hurry, as if I could outpace my growing fear. I found Mother stooped over the oxygen tank by her bed. Incontinence pooled on the floor, a heated mud pack tracked by to-and-fro footprints and the wheels of the oxygen tank rolling from the bathroom to her bedside. Images of my father's last week, the diapers he�d needed, filled me with dread. I took a huge breath and when I released it, I hugged my dear little mother gently and gently kissed her cheek before I leaned down to check the oxygen tank.

"Do you believe this?" she exclaimed, hoarse from trying to breathe, and perhaps from embarrassment. I�d never seen her like this before, she now the child.

I handed her the clear tube, watched her insert it, returned to the tank and spun the dial, trying to regulate the airflow. "This good?" I asked. When she nodded I left her and ran water until it was warm, bringing her a wet washcloth, soap and towels. I turned back to her closet and dug out a diaper from my father's supply. I handed it to her and helped her into a robe. I helped her onto the bed.

Once I was sure her oxygen was still working and that she looked secure, I ran to the back hall for a pail and a mop and raced back. I stuck the pail under her bathtub faucet and while it filled, I watched her. She looked like an elf perched on the bed, dwarfed by her now too-large dressing gown. I turned away from her to clean the floor, but when she gasped I dropped the mop and looked at her. She straightened her shoulders; her manner was regal as she whispered, "Have you ever for one moment thought you'd be doing anything like this?" Her arm waved with eloquence toward the mop I held.

"I love you," I cried. "All I can think about right now is helping you to get comfortable."

While I rinsed the mop, from the corner of my eye, I saw her disconnect the oxygen and start across the room. She fell. I raced to the tank, had trouble getting it on the carpet, shoving it to her side. "That tank's a panzer," I sobbed, sliding the tube into her mouth. I grabbed the blanket from the chair to cover her, that blanket no doubt her goal. We couldn�t get her back on her feet so I wrapped her up in the blanket and watched her curl up on her blues and white rug.

I stood up and hurried to call for help and get her some pillows, doing both at once.

"If you call nine-one-one, they'll take me to the nearest hospital, not to one my doctor has privileges at," she rasped.

"I can't carry you."

"Then call, but make sure they take me to Backridge."

The ambulance service made me promise to sign numerous papers, to have the doctor call them. They made me repeat my credit card number several times. Wild by then, I cried, "You'll get nothing if you lose the patient, and you will if you don't come RIGHT now."

I was shaking because I was livid, and so afraid for Mother.

I tried to help her back to bed without success. I retrieved another blanket and laid it on top of the throw that covered her, waiting with her on the floor in silence. Her head on my breast, my arms around her, we silently rocked together until the doorbell rang.

I let them in and dressed in a rush; I let Flyer out and signed endlessly parading unread forms. I watched as two brawny women and one stooped man huddled over my mother, hiding her from me. They bent over her for what seemed like forever. And it seemed like forever until I followed them out of the driveway, my car�s air conditioner and radio blunting the scream of the siren.

Hours later, five jelly doughnuts later, endless cups of coffee later, and two frantic calls � to Michael and to Maggie, Mother's doctor told me he thought she'd pull through.

And at last he allowed me to see her.

She was rigged with tubes and the hideous green oxygen mask that had so upset me last January.

Her voice was a whispered scratch on a blackboard, telling me I looked tired. Her skeletal fingers rose and fell so slowly that awareness of her weakness was impossible to deny. But she�d pull through. The doctor had just said so.

I sat with my mother through the day, leaving only to feed and walk Flyer. At four my mother pointed to the door. "Go home," she croaked, a faint smile impressed upon her lips. I couldn't leave her. But by dinner she grew insistent and insisted that I leave.

"Please go," her nurse entreated. "Even the slightest stress is dangerous to her."

I kissed my mother and as we hugged, I said I'd see her in the morning. Home, I called Michael and Maggie again, somewhat comforted by their assurances and good will.

Nausea woke me before night shifted into dawn. Between rounds of wretched sickness, despair joined fear. The thermometer registered one hundred and one. I couldn't go to the hospital. I couldn't see my mother.

I called my mother at eight. She was asleep, her nurse said. She said the night had brought my mother restless pain and confession. The nurse said that my mother had said she knew that she was dying and that she was glad, glad! that she wouldn't survive the hospital.

I called Michael. He booked a seat on a plane scheduled to land at eleven-fifty p.m.

I called Maggie.

When I phoned the hospital again, the nurse said Mother had turned away visitors, that she�d refused to speak to anyone on the phone. When she told my mother I was on the line, I could barely hear my dear mother say, "Ask her to bring my lipstick." I can�t come, I cried, and described my night to the nurse. "Please tell my mother that she has to talk to me! I'm sick and I need her," I cried.

Mih-the wanted her lipstick. She wanted to see me. She wanted to put on a good face.

I waited while the nurse gave her the phone.

Mother�s voice was a threadbare murmur. We spoke of loving each other and then the nurse came back on and I told her my brother was coming.

Dozing in and out of nausea, I was startled when the phone rang. It was the nurse, agitated, flustered, apologetic. "Your mother overheard me tell the night nurse about your brother's arrival. She's very angry. If your brother comes, I can't be responsible for your mother's health. I'm sorry . . . "

Michael had to come, but perhaps more for me than for Mih-the. I made myself dial his number. Cindy said he'd be landing soon at O'Hare to connect to a flight to Ft. Lauderdale. Good. It was out of my hands. But I called O'Hare and left an urgent message. Michael soon responded and I expressed the nurse's fears, silently urging him to come anyway. He heeded the nurse's caution.

My phone rang again at seven-fifty a.m. My mother's doctor said, "She died a few minutes ago. I'm sorry."

I called Michael, I called Maggie, and then I threw up, tears and vomit flooding the wastepaper basket beside my bed.

My brother and sister reached Florida hours later. Even with them, I still couldn�t really believe that our mother, Blanche Steinhorn Obletz, had died that morning, June 23, 1987. Cindy, Jacob and Eta came down the next day. Maggie stayed with a dear friend of our mother�s who lived on the other side of the circle across from the house.

Michael took me back to my rental for a change of clothes and brought me back to what was left of our immediate family. We banded together in the house of our parents. Our muted voices violated the silence and yet, when no one spoke, I feared that the pain inside me would deafen me.

Dr. Richard's prescriptions numbed me, but the searing core of reality wouldn't surrender to them. Only in sleep could I escape knowledge. I couldn't stop thinking about Mother being alone when she died, alone when death came for her, alone in a sterile place with no family to ease her departure.

No one had warned me that she had had a "mild" heart attack in May, which had left her with little heart to go on. I'd mistaken the waning of her life for recovery, her fatigue for a rebuilding of resources. I hadn't known that she was dying, that she knew she was dying, a fact she'd revealed to a stranger, not to her daughter, not me.

But oh how glad I was that I'd been there for her in her last days. How glad I was that both my parents knew how much I loved them, admired them, honored them.

There was nothing left unsaid between us.

And for that too, I was glad.

Because our parents hadn't wanted a funeral, the next evening we lit candles for them and burned photographs of them in a private requiem on the terrace of their home. We toasted them as their images curled in flames. Champagne and ashes. And then we feasted on a chocolate bar, their favorite kind.

Light shone onto the terrace through the dining room windows and the flames of the two candles cast flickering shadows on the faces of Michael, Maggie, Cindy, and upon the faces of Jacob and Eta, the grandchildren of our lost creators. Their eyes were set in the darkened circles of sleepless lamentation, tear-bright, brown and blue, two generations in mourning. And as I gazed upon our small circle, I felt heartbreak lift in our being together, spiritually entwined by memory and bloodlines, embalming my drug-dazed, grief-choked un-meetable need.

Our voices sounded distant and unfamiliar as we spoke of missing them, of times together. Memories couldn�t bring them back.

I couldn�t escape my terrible awareness of the awful empty space that they�d left, reverberating within me in irreclaimable echoes.

The breezes that came through the terrace screening that night were moist, carrying the sound of waters from the canal and insects from the grasses and birds from the curving of branches. I was so tired, the shell of me numbed yet seeming brittle. I couldn�t let my family see the unraveling of my emotions and wearily I rose, kissed each one good night and went to bed, leaving them on the terrace, sleep overcoming me in the bed my parents had shared, oblivion induced by medication, Flyer curled in a ball by my head.

* * *

There was work to be done in the house my parents had left behind. Treasures to divide, to pack, to ship at a later date to Milwaukee, Buffalo and my rental in Florida. The division went easily, and in the case of a rare contest, we flipped a coin, a manner of resolution our father had employed whenever reason couldn't brook argument.

And then there was departure for Milwaukee and Buffalo and I was left alone in Florida, the wounds of death still raw, bandaged by massive doses of four major mind-altering drugs. And by my mother�s family, her first cousins, their children and grandchildren.

The death of my father had numbed me. The death of my mother had shocked me, a primal violation of protective denial, stripping bare layers of emotion, tears brimming not flowing, opening me to suggestion � I had no will of my own. I was without my foundation, that knowledge crushing, despite medication. Yet, in this inundation of grief, I felt no anger, no frustration, no hatred, only the occasional rise of anxiety, which Xanax soon quelled. And most days I spent dinners with my parents� friends and family, centering me in the loving respect and sense of humor that we had shared with Blanche and Clarence.

Cousin Jerry and his sister Adele came with me to my parent�s house until there were no more papers to sort and things to give away. Reggie and Fred and their endearing bright children and I saw each other at least once a week, often for dinner one night and a movie and dinner on another. And Wendy and Abe in Boulder, Colorado, for three weeks in an environment I had never shared with my parents, surrounded by glorious mountains and lofty blue skies. Abraham had tousled blonde curls, an adorable face, an inquiring mind, and he adored Flyer. He always wanted to walk with us to the foot of the mountains not too far from Wendy and Abe�s natural wood frame home, more windows than wall space, each view connecting me to the beauty of Mother Nature in grand dress.

Eventually, too soon, back to reality. I never went to my parents� house alone, so altered was it physically and metaphysically, so painful were its echoes that rang hollow, rang lost.

I ached to move back to Chicago, but my home there was leased till the following August and renting there instead was an insurmountable expense. And it was July, not October, when most rentals become available.

Thoughts of Jess possessed me, the years of our friendship, our severance. She'd been the General in our war against anxiety. She'd grown used to command, yet my growing confidence within mental disorder had made me fight my dependency on her, making me fight her tendency to control me. Her intentions had been honorable, but deeply resented. I'd believed that I knew everything there was to know about madness, that I knew more about myself than I needed to know, and that I knew all too well those facts which I could neither change nor accept, facts she'd recall to me by her presence in my life more than by anything she said or did. It was her strength, and her hold on positive views that I no longer could witness. And though, weeks after our parting, I'd tried to revive our relationship, her silence had been a reprieve. We'd needed to break away, to separate the strands of our friendship that had become so entangled in the extremes of imbalance that they'd begun to strangle us. When we last met, she'd said I'd changed. I�d thought that she had. But she was right. I had changed. I�d lost sight of the good in life, sinking deeper and deeper into the blackness of depression as the hold cancer had on my parents strengthened.

But now, in my need to avoid the pain that memories of my mother and my father awoke in me, for the first time, I understood just how great the distance had become between Jess and me. No one could live too close to my black soul for comfort; my plot in Chicago had become a Bermuda Triangle.

And yet, not once had I felt abandoned by her, or that she had wished me ill. And Jess had loved my parents.

She'd want to know. And I needed to share my grief with her.

I wrote Jess and I mailed the letter. Her response came quickly and it was beautiful and supportive. Loving.

I called her and we talked, and we talked � for hours it seemed.

The reconvening of our friendship anchored me in the seize of loss.

THE SPARROWS SWELL

AND SILENCED BY BLAZING GRIEF, BREAK

STORMING-SORROW THUNDERING AT SEA

DROWNING, DROWNING

MEMORY SOARING

OH PHOENIX.

Summer 1987

Self-Portrait 1987 oil pastel on 8x5 gesso board

CHAPTER FORTY

Fear stormed me when my father called before five on a weekday afternoon. Before I could question him, he said, "Patrick-a, please get down here as soon as you can."

The meaning of his words sucked out my air and dropped me to the sofa.

"Your mother's in intensive care. Congestive heart failure. She's holding on. Michael's already here and Maggie arrives at five. Make your reservation now and I'll call you back, and Patchey, leave the return flight open."

Agreement ended this awful conversation.

A hot ringing filled my ears as I looked up the airline number. I was again outside my body, as if I were watching myself book my seat. My sneakered foot was a blur at the end of my swinging leg.

The first available plane landed at midnight.

She'd be dead by then.

My injured foot fell to the floor, the shock of that pain unnerving me, hurling me back into my body.

A boneless despair enveloped me, disorienting me, triggering aimless anxiety. My eyes fled from object to object in my sunlit living room. I was stopped by a silver framed photograph of my parents.

I hurried to the kitchen and filled my glass with seltzer. I carried the bottle and my glass to the bedroom, darting through shadows that darkened the room, familiarity concealed.

Flyer curled on my breast when I settled beneath the comforter. I hugged her. She licked my face and hot tears sprang from my eyes. Suddenly I was choking.

Shock turned into electric joltings that made my skin crawl through chilling waves of fear.

I found myself dialing Susan�s number at work.

"Patricia, I'm taking you to O'Hare. As we speak, I'm putting files in my briefcase, telling Sally that I�m leaving and then I�m heading for your house. Why don't you start packing?"

"Don't hang up right now, please, Susan . . . "

"Your mother's fighting, your father said."

"But Maggie will be there, too. They've never had us in Florida at the same time before. Never. Don't you see?"

Call waiting bleeped, we said goodbye, I swallowed seltzer and answered my father's summons.

He said he wanted the whole family together, that he was tired. He never

mentioned fear.

Our exchange was brief and unmarked by tears.

His voice had sounded old, and uncertain, not like my father at all. I dropped the phone in its cradle. Mih-the was too young to die.

Anger absorbed my despair, anger so raw it frightened me. And then swooping anxiety turned anger into panic.

Lightheaded, shaking, I shook a Valium from the vial and swallowed it, focusing on Maggie. We hadn't talked in four years.

How was she taking this news?

Waves of despair rolled through me, anxiety cresting, not breaking. I couldn't let myself think about Mih-the.

Maggie stirred sentiments that were wary, and colored by antipathy. I didn't want to see her. Certainly not like this. Not now, not with Mother �

Punishing, back-heaving sobs, abrupt and awful, drowned the room in wounded sound. Flyer whuffed, and with hands that visibly trembled, I brushed the fur on her back with my palms, my cries diminishing, not yet subdued.

I had to pack.

I stared at the red room closet door, my purpose there momentarily forgotten. Urgent need prodded me to reach to the top shelf and grab a suitcase. I slung it on my bed and unzipped its compartments. As if by rote, I raided the bathroom medicine cabinet; I swept pills from my night table into a zippered bag. I collected vitamins and the morning�s Rx army from the kitchen drawer, sealing the vials in a plastic bag.

I was folding clothes when Susan rang the bell.

She offered to keep Flyer while I was gone. I hadn't even thought about her.

Throughout the flight, my constant fight to breathe tightened my muscles to a pitiless pitch. The endless flat blackness of star-pierced night filled the window. It looked as cold and as treacherous as the thoughts that flattened my feelings.

She'd be alive. She'd be dead.

Maggie would be there.

We'd be face-to-face.

Facing death.

The plane tilted nose-down. My stomach rumbled, it hummed and it heaved like bees meeting in their hive.

My brother Michael greeted me at the gate. He was alone.

"She's holding on," he said and hugged me. "And Maggie and Dad are in bed."

I almost missed the twinkle in his eyes acknowledging my relief that I wouldn�t have to face Maggie tonight.

I took his arm, watching our feet traverse the terminal.

"Cindy and I picked a good time to come down here."

"You sure did, but where are we all sleeping?" I cried, visions of sharing a room with Maggie tightening my throat�s existing constriction.

"Cindy and the kids went home this afternoon, Maggie's in the guest room, and I'm in with Dad, leaving you the office."

At the house we whispered good night and parted. Valium, lithium, Norpramine and Motrin flowed with renewed strength through my system. Slowly the rising tide of sleep raised me from the shoal of awareness.

"Good morning, Patrick-a," my father said, waking me and clasping my shoulder.

"Daddy," I cried, flinging my arms around his neck, wading through the haze of medication. "How is she?"

"She's still fighting. Hurry up and get dressed, we're going to the hospital."

It was six forty-five a.m. I staggered off the mattress, sleep starved and drugged, and dragged on pants and a shirt from the suitcase.

Maggie was in the kitchen.

I pushed myself across the threshold. "Hi, Maggie."

"Hi." Her tone was friendly. There was pain in her eyes.

"Did you see her yesterday?" I moved toward her and then turned my back to her, removing orange juice from the refrigerator. I filled a glass and swallowed each pill separately, straining to hear her answer.

"She looked really sick," Maggie said quietly. Her hair was short again, whorls of near-black traced by a few faint lines of grey.

"How do you think she really is?"

"I think she'll make it � the doctor didn't think she'd get through the night." Her voice withheld conviction.

"Let's go," my father said, allowing Michael to take the car keys. I couldn�t recall Michael ever driving when our father was in the car.

No one spoke on the ride to the hospital.

I stared at the back of Maggie's head. Family crisis forged the only link between us, a link strong enough to treat hostility. I inched forward until my elbow rested on the top of the front seat. I smoothed the curls that swung away from my brother's neck.

Maggie repeatedly clutched then released the oversized bag in her lap.

I sat back, eyes dropping to my own lap, to my own knotted hands. I forced my hands apart and took my father's hand. The face he turned to me looked so sweet, and so sad among his tired lines.

We were stopped at the doors of the intensive care unit. It was too early, the nurse said, pointing out the visiting hours sign.

"Her doctor will let us in before nine," my father wearily announced, turning back to the waiting room, sinking into a chair, as if his legs could no longer stand him upright. He looked grey, as if the room had infused him with its dominant color.

Maggie began working on the sweater she was knitting; her foot, crossed over a leg, kicked the air faster than her needles flashed.

Sweat oozed from my palms, my upper lip. My ankle throbbed, an aching hot insistence. Tears ran, hot desolation translating raw emotion. Alarm exploded in my mind, splintering fragments of breathless soundless screams, divorcing body, mind, sense. Up became down and down up, and everything in sight was separating. I clenched my eyes shut and still my vision switched and jump-shifted, colors flashing, like the delusion conjured by expressway panic.

"Patricia, sit up straight," I heard my brother demand as he gripped my shoulders with one hand, bracing my back with the other. "And breathe � slowly, one and two and, breathe, Patricia, breathe. In, out, in, out . . . good . . . "

"Don't you have a doctor down here?" Maggie asked me.

"Here's a quarter, Patrick-a," my father said, reaching into his pocket, handing me the coin.

Michael looked up Dr. Richard's home number and dialed, handing me the

receiver.

I stumbled through a description of the state of my mind, steadied by Michael's hand on my shoulder and by Dr. Richard�s voice.

He said he'd call the hospital pharmacy and order a prescription for Xanax, an anti-anxiety pill, he added. I was to take no more than six a day, and try to stick to four.

My brother retrieved the medicine and in his absence, I held my father's hand, practicing deep breathing, trying to reject thoughts that tried to pass through the doors of the ICU.

Xanax was a smooth and tiny lilac oval. It left a metallic bitterness in my mouth. Soon my emotions detached from my senses, making me an observer again, unable to participate. But breathing was still difficult: short breaths and shallow.

At seven-fifty, my mother's doctor arrived and authorized the nurses to let us see her, two at a time.

"You go first," I said, claws of anxiety unsheathing.

When my father and Maggie returned, Michael said, "Up and at 'em."

I rose, my knees a gelatinous bridge between thigh and calf. Faltering, I took Michael's arm and approached the oversized double doors to intensive care. Slowly they swung open.

Michael turned into the first doorway. The room was washed in twilight. It hummed and it clicked. It inhaled and exhaled. It smelled antiseptic. I hung back, eyeing the labyrinth of tubes extruding from my mother, her form inert and spread-eagled. Michael pushed me forward.

A hideous tinted-green mask covered my mother from nose to chin. A tube was shoved through her lips, forcing down one side of her mouth, garish and inhumane.

My mother dragged her eyes to meet mine. I didn't know what to say to her. Pressure to say something forced words out of my mouth: "I'm sooo glad to see you, I'm so glad to seeeee youuu," I cried, my voice careening up the scale of hysteria.

"Patricia . . . "

My brother's tone, and my own lack of control, sent me racing from the room, hand clamped to mouth to silence my screams.

"What's wrong?" Maggie cried when I reappeared. "Is . . . is she . . . ?"

My father came toward me.

I shook my head no and motioned them to take my place. Alone, I hurtled into a corner of the lounge, overcome by wrenching sobs.

In less than a month my mother had become a fragile and violated thin hull. The transformation was too great a leap, even under the ministry of Xanax.

"Are you all right?" Michael was beside me, cupping my elbow, turning me to face him.

"It was . . . too much � " I was shaking all over, new tears joining the old.

"It is shocking," Michael said, calming me, raising me from the floor, hugging me, helping me to the grey leather sofa. "You have to see her again," he insisted gently. "For her sake, and yours. Feel up to it now? No? Let's go for a walk outside. You can smoke a cigarette � if you have to . . ."

I limped after him to the bank of elevators and then out into the hot Florida sun.

All too soon it was time to retrace our footsteps. All too soon I was again at the foot of my mother's bed.

"You, you look like an astronaut with all this, this . . . " I flung out my arm to encompass the complicated-looking equipment. I found Mother's hand, frail and skeletal, and I held it in my own.

"I saw space yesterday . . . " my dear mother rasped behind the mask. And then she stared into my eyes. "Your hands are cold, honey, so cold . . . "

"Warm hands, cold heart, and you're warming me up like you always do."

The nurse said my mother needed to rest. Michael circled my shoulders with his arm and we left her.

After a hurried, near wordless lunch, we returned to the hospital. Now and then Maggie and I would go outside to smoke a cigarette. "Things are looking up," she said, backlit by the sun. "The doctor seems encouraged by the fact she's still alive."

"Are you?"

"She's going to come through this. And I can't tell you how much better she looks today than yesterday."

"I can't imagine her looking any worse. I can't imagine it . . . "

"Trust me," Maggie said, sparking the challenge that had divided our past.

"Believe me, I'd like to." I drew closer to her, stumbling, almost falling. I cried out from the pain that shot into my ankle and Maggie spanned the gap between us, gripping my arm, propping me upright.

Maggie helped me return to the lounge. The men in our family faced us from two armchairs as the elevator doors opened. We sat on the grey leather sofa, and I moaned, unable to muzzle my pain.

"Let me see that foot," my sister demanded, hovering while I unlaced the sneaker, removing it, and the sock.

"Let's see the other one," she prompted, examining without touching either foot. "The right one's swollen," she judged finally, sympathy in her tone. "What did the X-ray show?"

"I never went to a doctor."

"Oh, Patrick-a, how could you be so careless," my father exploded.

"It's just a sprain."

"I'll get her to a bone man on Monday," Michael said. And he went back to the phone and looked up the name my father gave him, calling and gaining an appointment.

Once more in the room with my mother, I watched drowsiness lower her eyelids again and again, despite her resistance. She hadn't slept since entering the emergency room yesterday at daybreak, she said.

The four of us dined in a restaurant near the hospital. Little was said. When it was time to leave, my father stood. My father fell face-first to the floor.

I whirled away from the horrifying sight, hiding in Maggie's comfort, unable to watch.

Michael was so solid in the face of collapse.

But it seemed like forever until Maggie said my father was in a chair.

Maggie and I rode home in the back seat of the car.

When Michael and Daddy went to bed, Maggie and I went to the terrace, sitting silently, smoking one cigarette after another, until there were eight in the ashtray. "How's the foot?" she asked.

"Not too bad." But it hurt. Oh how it hurt, how it pulsed hot and throbbing against swollen-stretched skin. And I knew that every pain I was feeling was centered in that ankle.

"What do you think happened to him?" I questioned, afraid of her answer.

"He's tired. He's been through a lot."

"Do you really think that's all it is? He's lost even more weight since early December."

"He's been through a lot," Maggie repeated with confidence and with firmness. "We should get some sleep, too."

On Monday, the critical stage was over and Mother was moved into a private room, its attractive furnishings oddly juxtaposed to the equipment that guarded her life.

Relief fed conversation as Michael took me to the ankle specialist. My foot wasn't broken; it should heal soon, the doctor said. He wrapped my ankle to the knee, the bandage to be worn three weeks.

My father looked gaunt; even his voice was thin, I noticed when we returned to the hospital.

On the terrace that night with Maggie, I again voiced fear for him.

"You worry too much," she advised.

"But you can see he's in rough shape. How can I not worry about him?"

"And you think I don't?" she snapped. When I flinched, she said, "Sorry. I'm on edge."

"It's terrifying."

"It was only Friday that the doctor was planning Mother's eulogy." Her shrug said everything.

When I darkened my room that night, I thought about my mother; I thought about my father. A plan began to form.

Waking was a slow emergence from a dark, comforting place. It was five-forty. I decided to call the hospital, my heart tripping to a faster and faster rhythm as I set my hand on the phone, still unable to believe Mother was out of danger.

Before lifting the receiver, I heard someone walking down the hall to the bathroom. I opened the door. My father seemed surprised to see me. And then he smiled.

"Did you call?" I asked softly.

"Yes. She�s doing okay. But I knew your mother wouldn't dare die before me. She's ten years younger and she has my best interests at heart." He shook his head; he smiled. "And I had a good night's sleep. How about you?"

"Daddy, I'm moving down here. I don't know why I didn't agree when you suggested it before." There. It was out. I couldn't retract it. "I'm going to lease my place in Chicago and rent one here � "

"I'm glad you want to come down, but first you have to finish the word processor course." His tone was inflexible.

"That's not till the end of May!"

"You can come down then," he said firmly.

"Okay, okay. Okay!" I hugged him. But it was only January. They needed me before the end of May.

He went on down the hall and anxiety claimed me; I fumbled for a Xanax and the water by the sofa bed.

While my father showered, I went through our conversation again and again, resolve strengthening. I wouldn't lose my home if I rented it. I wouldn't be committed to Florida. I could live anywhere as long as I could go home again. And I'd be near my parents, a walk away, faster by car.

When Michael and Maggie woke up, I told them my plan.

"The halt leading the blind," Michael teased and when Maggie laughed, too, I joined them.

Maggie left the next day, returning to Buffalo, city of our birth. Michael and I were going home Thursday. He'd finally convinced me that our father and mother could manage without us by then.

Susan thought the move to Florida was a good idea. Dr. Moline thought the move to Florida was a good idea.

I felt stronger than I could remember. I now had a reason to be alive.

On the flight back to Chicago, a short story began on a yellow pad. The story came slowly, a fictionalizing of Mother's congestive heart failure. I named it The Waning and in its writing I found solace. I found my true self, and an easing of horror.

The word processor came more easily to me, despite the missed week of classes.

Every day I packed two or three boxes.

My mother came home. Her cancer had been reduced by the chemo. So had her heart. She was feeling exhaustion not pain � the shingles had disappeared, too.

My anxiety was layered by three Xanax a day, not the six I'd needed in Florida, not the five, then four that I took my first week home . . . Home. The dismantling of my apartment gave it a strangeness that was unsettling, making abandonment desirable.

A married couple signed a lease during the third week in February on the condition that I paint my green walls white. It was no longer home once that was done.

============================================================

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

My father was nauseated.

He couldn't eat.

My father grew weaker.

When he was hospitalized for tests, my sister Maggie went to Florida.

Everything they put him through came back negative. The day after he got out of the hospital, Maggie flew back to Buffalo.

My father grew weaker. He needed a cane.

Michael, Cindy and I were in constant contact. Maggie and I spoke weekly.

My father grew weaker. He needed a walker.

I went back to six Xanax a day and increased my bedtime pills until they brought sleep to me. My breath was always short and shallow swallows of air, never quite enough.

A nurse came to stay with my parents. Her name was Barbara and she was big and strong, Mih-the said.

The word processor course took me into the Loop two times a week. Somehow I completed assignments, but when called upon in class, I couldn't remember what to do when.

I was relieved when Dr. Moline recommended that we see each other twice a week. His support reduced my fear by acknowledging its reality, as well as by acknowledging the awful limbo of new unanswerable questions.

Between sessions and school I packed, ink-stained from endless skeins of newsprint. My home became a series of paths through columns of stacked boxes, each filled, taped and identified.

Packing certain pieces took me back to moments of first possession, times of hope, hope that was bright before death became personal.

Packing was tedious. It gave me too much time to think. I packed thirty minutes, forty, took a break to write, call friends, pace, nap, walk Flyer.

It was the writing, it was the medication, it was the encouraging support of family and friends that pushed me forward. It was suddenly the last week in February.

My brother called. Our father had collapsed and his doctors didn't know why. He was in the hospital, undergoing more tests.

Michael said he had seats for us on a plane leaving at six and to meet him at O'Hare. Would Maggie be in Florida? I couldn�t breathe as I waited for his answer. She was leaving Florida that afternoon � she'd been down for a week's vacation, he reminded me.

I called Susan. She offered to take me to the airport; she offered to take Flyer.

Xanax chained me to the high diving board; I was afraid of its edge, the last foothold before the plunge into space.

It couldn't be that serious since Maggie was going home.

It wasn't that serious.

Maggie and I were in tune with each other now, allied by a common fear. And though she never asked about my writing or my friends, she did ask about my foot.

Since December, the foot had been swollen and painful. It would never get better I'd tell Maggie. Yes it will, she'd insist.

My father was home from the hospital when Michael and I arrived. We met Barbara, the nurse who now slept on a cot in our parents' room.

We went to see our father. He was propped by pillows and the raised head of the hospital bed. He was on Mother's side, next to the phone. This change chilled me and curled my stomach, muscles clenching so tightly that I couldn�t seem to fully catch my breath, almost losing the swift rise of bile that continued to sicken me.

His cane was in the corner, his walker parked within his reach. He smiled at us, returning our kisses. He didn't say much. Talking was difficult for him, my mother said, twisting the pain in my heart.

I took a seventh Xanax that night and woke in a drug-dazed fog. I added Xanax to my breakfast dose of lifelines.

Michael chauffeured our father to and from the hospital day after day. Those days seemed to swim by in a breathless hold of hope and fear.

My father grew too weak for the walker. A wheelchair was now parked by his bed.

When I looked into my father's eyes, the light of life was so strong that I'd forget how sick he was. But he wasn't sick, his doctors could find nothing wrong. He was just tired, just as his friends kept telling me. The disintegration of his body would stop; it always had. Oh but when?

There were no more tests for my father to take. He didn't dress again during that visit. Neither did my mother, but I was used to seeing her in one of her beautiful robes.

My father was alone when I went to sit with him one afternoon. He appeared to be asleep, but he opened his eyes and he smiled at me and, with effort, he raised his head; with effort, his lips worked, trying to form the word hello that finally came out into the open. "Hi, Daddy-O," I whispered. "You're pretty lazy these days, but I love you anyway, you know that, don't you?"

He nodded his head, and his smile when it curved into his face made me ache with love. But how could he just lie there? Why wasn't there a medical name for what was happening to him? "They say you have to use it or lose it � won't you walk with me?"

His head shook slowly, side to side.

"Oh Daddy, can't you?"

"Weak," he finally uttered.

He'd been so active. My stomach coiled, ready to erupt. I swallowed back the liquid rising in my throat and brushed his hair with my palm, sitting beside him, scratching the length of his arm.

He grinned. A full grin. His eyes lit up. He fumbled for his glasses and put them on. Oh how alive his eyes were in his tinged-grey face, cheeks sunken below the heaviness of his cheekbone.

"Patrick-a," he said, his voice rattling my name. And he held out his hand to me.

I took it. I gripped it hard. "Use it or lose it," I heard myself say again, and in the stillness of the room, my voice sounded harsh. "Oh Daddy, can't you try? Can't you? Come, I'll help you. You can walk around the bed � just in case you need to sit down fast!" I laughed, but it sounded hollow.

He nodded, turning back the covers. I helped him up, I slung his arm around my shoulders. I matched my step to his, one foot slowly forward, then the other. At the foot of the bed he gasped, he sank to the mattress, pulling me down with him.

"You were great," I cried, kissing his cheek, sitting beside him, huddled inside cold despair.

And then Barbara came in and she helped him back into bed.